Andrea Medici wrapped up three decades with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) late last year, around the same time Allecia Jones had settled in as a Foreign Service officer for the State Department.

Medici left her job nine months after becoming eligible to retire as a 56-year-old attorney-advisor. Hired in 1991 during George H.W. Bush’s administration, she worked in the EPA’s general counsel’s office in Washington, D.C., specializing in pesticide and chemical regulation.

“I do feel proud of doing that for a long time, and I believe I did my job well. At the same time, it was a mixed bag,” Medici says. “I did get what I would call burned out, particularly in the last administration.”

Jones, a member of Generation Z, has a two-year assignment researching the Haitian economy from Port-au-Prince. She arrived in Port-au-Prince in May 2022.

“I really enjoy doing the economic work,” she says. “There are real-world results that happen from some of the reporting and information that I’m providing to our policymakers back in D.C.”

It was one out, one in for the federal government, which has more than managed to keep up its headcount amid employee exits, despite longtime predictions that the federal labor force would be hit hard by a wave of Baby Boomer retirements. The federal civilian workforce increased from just under 2.1 million at the close of fiscal 2017 to nearly 2.2 million in May 2022, according to the U.S. Office of Personnel Management (OPM).

‘There isn’t any massive event that’s triggering federal retirement.’

Jeff Neal

That said, government agencies have long been hobbled by bureaucracy and slow to make hiring decisions, among other shortcomings.

“Nobody in their right mind would devise the hiring system like the one the federal government has right now,” says Jeff Neal, a former chief human capital officer for the Department of Homeland Security and a member of the National Academy of Public Administration. “It’s too complicated, it’s too lengthy, it doesn’t actually produce the results it’s designed to produce.”

Retirement Doomsday? Maybe Not

A long-predicted tsunami of retirements in the federal workforce has not occurred. Collectively, about 180,000 civilian employees retired from the federal government over the past three fiscal years. That’s a significant figure, but the number of new hires has more than tripled that—nearly 652,000—over the same period, according to OPM data.

“That whole ‘retirement tsunami’ idea was sort of a flawed concept to begin with,” Neal says. “Tsunamis happen because of a single event that causes a massive change in the water, and there isn’t any massive event that’s triggering federal retirement.”

As of September 2022, 14.3 percent of the federal workforce (nearly 280,000 employees) was eligible to retire, OPM reports. Historically, however, not everyone leaves as soon as they are able. Many public servants tend to stick around for years after running out the clock, Neal notes.

“People stay around for different reasons. Some people are even more inclined to want to stay in the agency they’re in once they’re eligible to retire,” he says. “Now they know, ‘I’m here because of my choice, not because I have to be here.’ ”

Even Medici, a top-grade employee who literally counted down the days until she was eligible to retire, did not do so immediately. Rather, she stayed on for several months as a full-time union steward for the National Treasury Employees Union Chapter 280, which represents about 1,500 EPA employees. She first assumed that role in 2019.

“It was not just a refreshing change, but a really rewarding change,” Medici says of her union work. “I was helping people directly, and they appreciated that.”

Changing Demographics, Nonetheless

As the competition for workers heats up, federal jobs come with significant perks. The government offers pensions and a paid parental leave policy that is still rare in the U.S. Also, many government positions offer mission-driven work that may be especially appealing to young people.

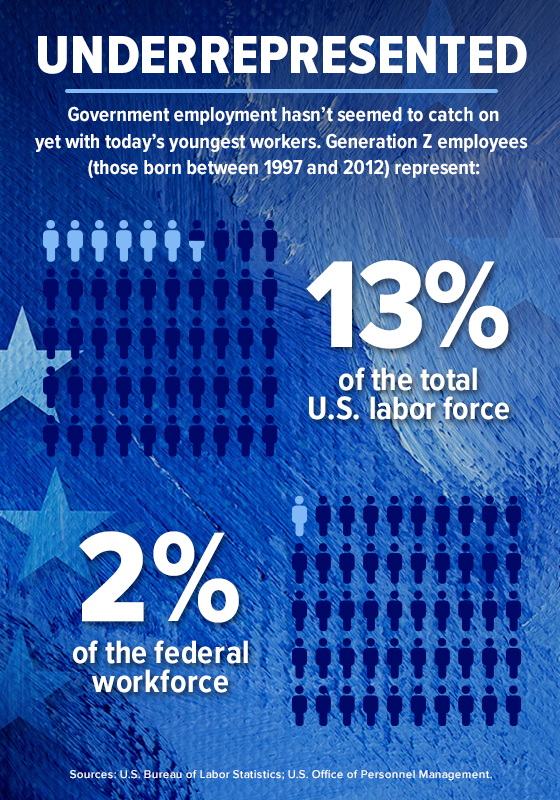

Still, the feds are seen as being hobbled by bureaucracy and slow to make hiring decisions, among other shortcomings. For example, members of Generation Z (those born between 1997 and 2012) are generally expected to be picky about where they work and not inclined to wait months for an offer, which is a common problem among federal agencies.

These so-called digital natives are known as the most diverse U.S. generation ever, with nearly 50 percent identifying as nonwhite; not surprisingly, they value inclusion. They also will require a work/life balance that their Millennial and Generation X predecessors did without, says Mark Beal, a Rutgers University assistant professor of professional practice and communication who studies Generation Z.

“Gen Z is looking for the opportunity to work remotely—not necessarily full time, but the opportunity to have the hybrid situation,” Beal says.

Another reality for bosses is there may not be as many Generation Z members to go around in the U.S. labor market. Figures vary, but there are an estimated 65 million to 70 million members of Generation Z in the U.S., slightly less than the Millennial count of 72 million.

Currently, members of Generation Z account for nearly 13 percent of the U.S. labor force, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. But they are currently only about 2 percent of the federal workforce, according to OPM.

‘In the new world of work, retention becomes our No. 1 goal.’

Bradley Schurman

“For probably about half a century, we got really accustomed to having a readily available, relatively well-educated workforce that was cheap and at our disposal,” says Bradley Schurman, a consultant on older generations and author of The Super Age: Decoding Our Demographic Destiny (HarperCollins, 2022). “The new demographic reality doesn’t look quite like that, because there just aren’t as many Gen Zs as there were Millennials. It’s simply a shift in the labor force participation rate.”

In the coming years, people ages 65 and over will represent at least 20 percent of the population in many developed nations, Schurman says. U.S. employers will need to revise their notions about retirement and be open-minded about what older Americans can accomplish in the workplace, he says.

“In the new world of work, retention becomes our No. 1 goal,” he says.

|

|

U.S. workers continue to demand greater opportunities to telework or do their jobs completely remotely. Federal human resource officials say they are not oblivious to this trend. The government’s central job-listing site, USAJobs, flags positions that may be done remotely in hopes of tapping the widest talent pool. And the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) is examining how telework and remote work will fit into the future of the federal workforce. The U.S. chooses the refugees it accepts and sets limits on the number of refugees it allows into the country each year. Before being accepted, refugees are screened by various government authorities, including the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Department of Defense. “We have learned and certainly have seen that in order to be competitive with other sectors, we need to have workplace flexibilities, and that is going to be something that’s important for the next generation,” says Margot Conrad, an advisor to OPM Director Kiran Ahuja. The percentage of federal employees eligible to telework at least some of the time has risen from 33 percent in fiscal 2011 to 50 percent in fiscal 2022, according to a report from the OPM issued late in 2022. Not surprisingly, the percentage of teleworking federal employees dramatically increased at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic—from 22 percent in fiscal 2019 to 47 percent in fiscal 2021. Proponents of telework and remote work (doing one’s job entirely away from the office) say these options promote greater work/life balance, could help in the retention of employees and could reduce the government’s real-estate footprint, among other upsides. |

Holding On to Good People

Some observers find the recent uptick in the size of the federal labor force surprising, given the Trump administration’s turbulence and the COVID-19 pandemic’s disruptive impact on the U.S. labor force. The former president’s tenure included a lengthy government shutdown, the de-emphasis of certain executive agencies and attempts by the White House to remove job protections for tens of thousands of federal positions.

But when it comes to retention, the federal civilian workforce is not in crisis mode, according to an analysis from the Partnership for Public Service (PPS).

In fiscal 2021, the governmentwide attrition rate was 6.1 percent and included a roughly equal number of “quits” and retirements. That level was consistent with the federal attrition rates from fiscal 2019 and 2018, if slightly higher than the 2020 rate of 5.5 percent, the organization reported.

Some agencies were losing employees at a greater clip. At 7.1 percent, the Department of Veterans Affairs had the largest attrition rate among agencies in fiscal 2021, the PPS says. Health-related occupations in government had a higher-than-average attrition rate—also 7.1 percent.

Despite notions that its employees were unhappy during the isolationist Trump administration, the State Department did not experience a mass exodus. Its attrition rate actually stayed in the 5 percent to 6 percent range.

Still, officials say, the department created its first-ever retention unit in hopes of preserving its core roster of 11,500 Civil Service members and 13,700 Foreign Service officers. Individuals in the latter category must retire at age 65 because of the sometimes-dangerous nature of international work.

In 2022, the State Department saw its largest influx of Foreign Service officers in a decade, officials say. Jones, the Generation X member working on a two-year assignment in Haiti, is among the newest hires serving in another country. As a Black woman from Oklahoma, she says she has had the opportunity to defy expectations some foreigners may have about Americans.

“When you travel abroad, [I’m] not necessarily what people think of as a quintessential American,” Jones says. “All of the conversations I’m having with people are very interesting because they’re learning a little bit about the U.S. culture through me.”

Gauging Morale

Not all government employees are satisfied with their work conditions.

Medici says labor-management rancor persists, even after the Biden administration took the reins of the government. And she feels there is a significant brain drain occurring through retirements, based on her observations at the EPA.

In the meantime, the American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE), the largest labor union representing federal workers, has said some areas of the federal workplace are dangerously understaffed.

Shane Fausey, national president of the AFGE Council of Prison Locals, told the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee last year that roughly 3,000 employees in the U.S. Bureau of Prisons were expected to leave by the end of 2022. He said only about 35,000 employees were actually staffing the prison system, even though the bureau was authorized in 2016 to have a staffing level of 43,369. He urged the Biden administration to restructure pay bands and offer retention bonuses. (AFGE representatives did not make themselves available for this article.)

At least collectively, morale within the civilian workforce appears to be fairly stable, according to the most recent Federal Employee Viewpoint Surveys conducted by OPM. On a scale up to 100, the broad metric of employees’ “global satisfaction,” which includes an assessment of pay and job satisfaction, has seesawed in the 60s and dropped slightly during the Biden administration. The composite figures ranged from 64 in 2018 to 65 in 2019, 69 in 2020, 64 in 2021 and 62 in 2022. (Seventy-two percent of the federal employees who participated in the latest survey skewed middle-aged or older as members of Generation X or Baby Boomers.)

“The numbers are not wildly different from one administration to the next,” says Neal, the of the National Academy of Public Administration. “It means, for the most part, federal employees are not highly political animals, even though they’ve been accused of that, and they do their jobs. Whoever is sitting in the White House has an effect—but not much.”

|

|

The government has taken a novel approach to hiring, retention and related federal workforce issues since the Biden administration took office in January 2021, say officials at the Office of Personnel Management (OPM). One of the first moves was to reorganize the Chief Human Capital Officers Council (CHCOC), a panel of top HR managers across the federal government, as well as a smaller steering committee. The smaller group sets meeting agendas for the council and serves as a “sounding board” for new ideas, says CHCOC Executive Director Margot Conrad. In an interview with All Things Work, Conrad and Carmen Andujar, OPM’s manager for recruitment policy and outreach, discussed some of the strategies that the federal government is using to keep the pipeline flowing with employees that reflect the nation’s diversity. They include: Taking a skills-based approach to hiring. Derived from a Trump-era executive order, the skills-based hiring concept allows hiring managers to weigh an applicant’s skills and competency over educational background for certain jobs. “Not everybody has a formal education, but they may have the skills to be successful in the performance and duties of the position,” Andujar says. The U.S. Digital Service, a technology unit in the executive office of the president, is an obvious fit for skills-based hiring, she says. Continuing the use of pool hiring. This allows multiple departments to share candidates who receive certification for a particular job. In the traditional model, siloed agencies post jobs and screen candidates individually. Several departments have used the newer “shared certificates” method as they filled thousands of jobs created under the recent infrastructure bill passed by Congress, Conrad says. Offering 10-year appointments to science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) professionals. Jobs with limited lengths of service work well with some project-oriented agencies, including NASA, Conrad says. “It gives them another tool when they’re doing their workforce planning,” she says. Increasing the number of paid federal internships so that young people can recognize viable career paths in government. Past experience shows that pre-employment opportunities offered by the federal government help influence people to enter public service. —M.R. |

Mike Ramsey is a Chicago-based freelance writer.

Explore Further

SHRM provides resources and information to help business leaders to help leaders stay ahead of federal workforce trends.