?Victoria M. Walker viewed her tweet as a way to put information in one central location to avoid answering individual inquiries from fellow reporters while on vacation. It didn’t work out that way.

The tweet went viral and was featured in media across the globe, including The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post and National Public Radio. What was this tantalizing bit of information?

Walker shared that she had been paid $107,000 a year as a senior reporter for travel website The Points Guy before leaving the position, and she was recommending that those applying for the job ask for a salary of $115,000, a signing bonus and relocation expenses, if applicable.

She thought only a few journalist friends would be interested in her tweet. “I wanted the people interviewing for the job to be able to advocate for themselves,” says Walker, who is now a freelance writer.

The fascination with Walker’s tweet reflects Americans’ hunger for compensation information. Some lawmakers and investors are taking action to make more data available.

A solid majority of employees (79 percent) say they want some form of pay transparency, according to Visier, a Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada-based maker of workplace software. At least 14 U.S. states and five cities have passed laws requiring such transparency. Institutional investors are also calling for more public disclosure. This year, almost 60 percent of Walt Disney Co. shareholders approved a request for greater pay transparency.

The movement stems from an overall desire for a fairer society in the wake of #MeToo, Black Lives Matter and the COVID-19 pandemic, which laid bare pay inequities in the U.S. Women and people of color are consistently paid less than white men, and transparency advocates insist that disclosing more salary information will better equip workers to negotiate for fair compensation.

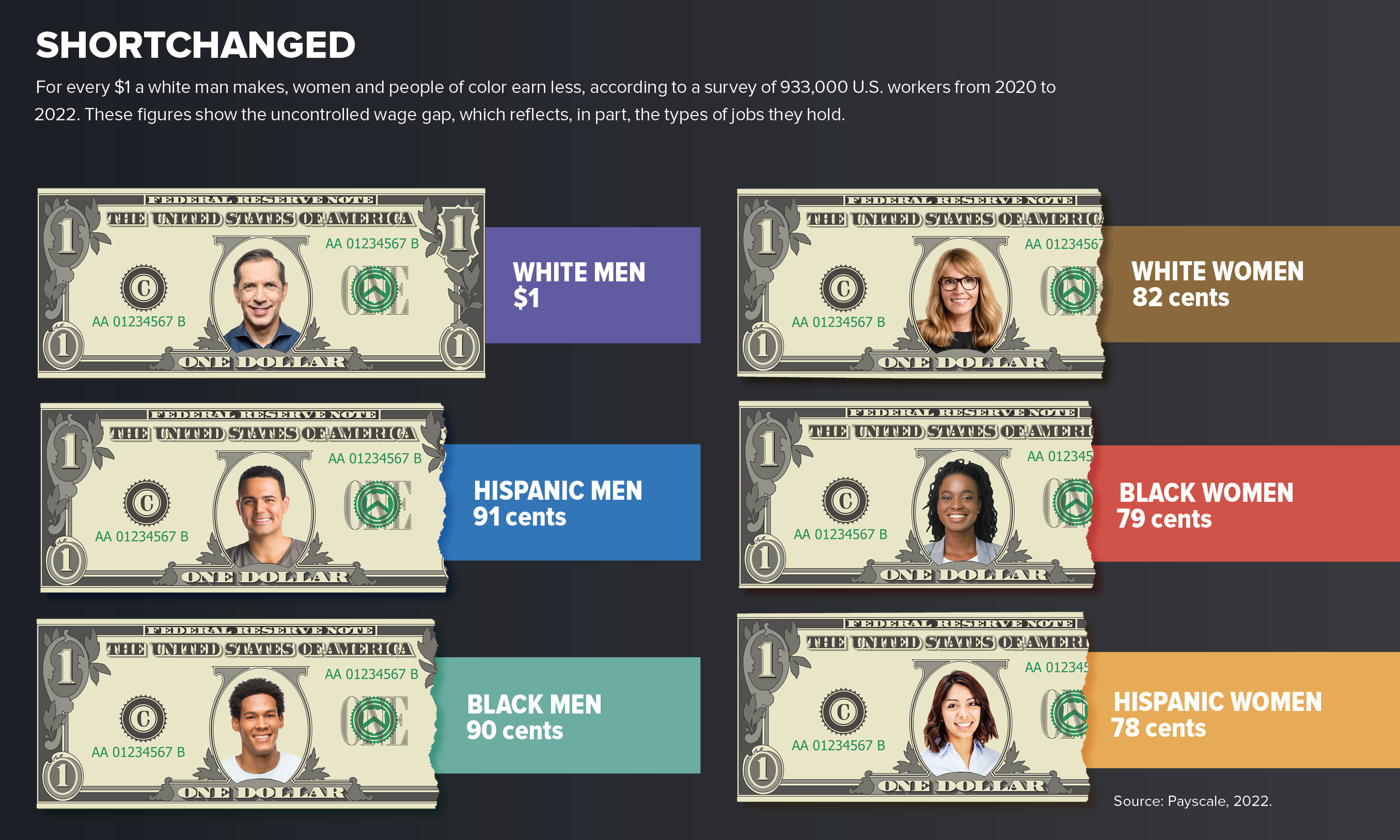

Women earn 82 cents for every dollar earned by men, according to a study released this year by Payscale. The gap widens when comparing white men to women of color. American Indian and Alaska Native women face the biggest disparity, earning 71 cents for every dollar a white man is paid. Hispanic women earn 78 cents, while Black women are paid 79 cents.

Meanwhile, Payscale found that Black men earn 90 cents for every dollar paid to white men, Hispanic men make 91 cents, and American Indian and Alaska Native men earn 88 cents.

These inequities have long left women and people of color with less buying power, and the gaps are especially pronounced during periods of high inflation.

“There is a plethora of organizations that have done the research [on pay gaps], and it’s the same message over and over and over again,” says Adriana Herrera, founder of PayDestiny, which provides tools that help people become better negotiators. “It just can’t be ignored anymore.

Secret Salaries

The problem, though, is that pay inequity is being ignored. Less than one-quarter (23 percent) of the 954 largest public companies in the U.S. in 2021 conducted some type of gender pay gap analysis, according to JUST Capital, a nonprofit in New York City that tracks corporate response to social issues. Of the 215 companies that studied the issue, only 75 reported the results of their investigations while 14 said they found no statistical difference.

In 2022, 43 percent of the 100 largest U.S. companies said they conducted a racial/ethnic pay gap analysis and 22 percent released their findings, JUST Capital researchers found.

“There’s no requirement for companies to disclose if they’re conducting this type of analysis in the U.S., so many don’t,” says Mariann Madden, co-leader of consultancy WTW’s North American Fair Pay team, which helps clients determine pay structures.

Madden says a number of companies are examining and adjusting their pay policies to ensure fairness but they’re reluctant to publicize results for multiple reasons. Among them: Many senior leaders believe discussing salary is taboo, and there’s no universally accepted standard of how to measure and report compensation information.

Companies also tend to push back against “anything that restricts what they want to do or what they think is best for their business,” says Lori Wisper, a managing director at WTW. Plus, she adds, companies worry that publicizing results will lead to lawsuits.

A Grassroots Movement

Hannah Williams is taking her fight for pay transparency to the streets, and then to the Internet.

In April 2022, the 25-year-old began pounding the pavement to ask people about their livelihoods, including their pay, and posting their video responses on TikTok and Instagram. In just a month, her @salarytransparentstreet account attracted about 1 million followers and 114.5 million views. The overwhelming response pushed Williams to quit her $115,000-a-year gig as a data analyst a month later to turn her passion project into a business.

“My goal is really to pressure and encourage corporate America and businesses to implement transparency across their organizations,” Williams says. “We can talk about pay all we want with our friends and family, but it really, truly doesn’t matter or have the impact we’re looking for until pay transparency is available across all departments in an organization, because then you’ll know” whether you are fairly compensated.

The Georgetown University graduate’s interest in pay transparency started last year when she was working up to 17 hours a day as a senior data analyst. Williams says she started thinking that her annual income of $90,000 wasn’t nearly enough. A Google search revealed that someone with her experience living in the Washington, D.C., area should earn more than $110,000 annually.

“It was a real blow,” Williams recalls. “Not only was I underpaid, but I was also not being supported in my job.”

Williams quit and found a better-paying position. She says the reaction she received from posting about her travails on her personal social media accounts convinced her there was a huge appetite for salary information. That’s when Salary Transparent Street was born.

She isn’t the only one providing salary information on TikTok. The app is loaded with individuals posting their own salaries online, while others coax strangers to reveal their earnings. In April, Adam Ali started American Income and has attracted 70,000 followers and 23 million views of his videos that disclose what others earn.

Many would rather keep such personal data a secret. Williams says half the people she approaches decline her invitation to speak up, adding that people under the age of 45 are more willing to answer.

Williams is preparing to take her show on the road. “I want to show salary transparency across America,” she says. —T.A.

Legal Woes

Last year, Syracuse University paid $3.7 million to five female professors who alleged gender pay discrimination after the university conducted a study revealing gender pay gaps. That study led it to pay $2 million to about 150 female professors in 2017. The five professors sued because they believed the pay adjustments were inadequate.

Employers “have the sense that it’s going to open up all kinds of exposure liability and it’s just going to cost them a fortune to address and resolve the issues,” says Garry Straker, vice president of compensation consulting for Salary.com, a provider of compensation data, software and consulting based in Waltham, Mass. “It comes down to the risk tolerance of an organization and the level of priority and commitment they have to address it.”

Increasing pay transparency does close pay gaps, according to some academic studies. However, it can also pull down overall pay and limit individuals’ ability to negotiate salaries.

In a study published earlier this year, business professors Tomasz Obloj at HEC Paris and Todd Zenger at the University of Utah examined the salaries of 100,000 academics over 10 years and found that greater transparency led to a 20 percent decline in gender pay inequity.

A separate study released last year by professors Zoe B. Cullen at Harvard Business School and Bobak Pakzad-Hurson at Brown University examined the salaries of 4 million workers living in states that protect employees’ right to discuss their compensation and found that salaries overall fell by about 2 percent, with less of a reduction in occupations with high unionization rates. Employers refuse to pay high wages to any one worker to avoid costly renegotiations with others under transparency, the researchers determined.

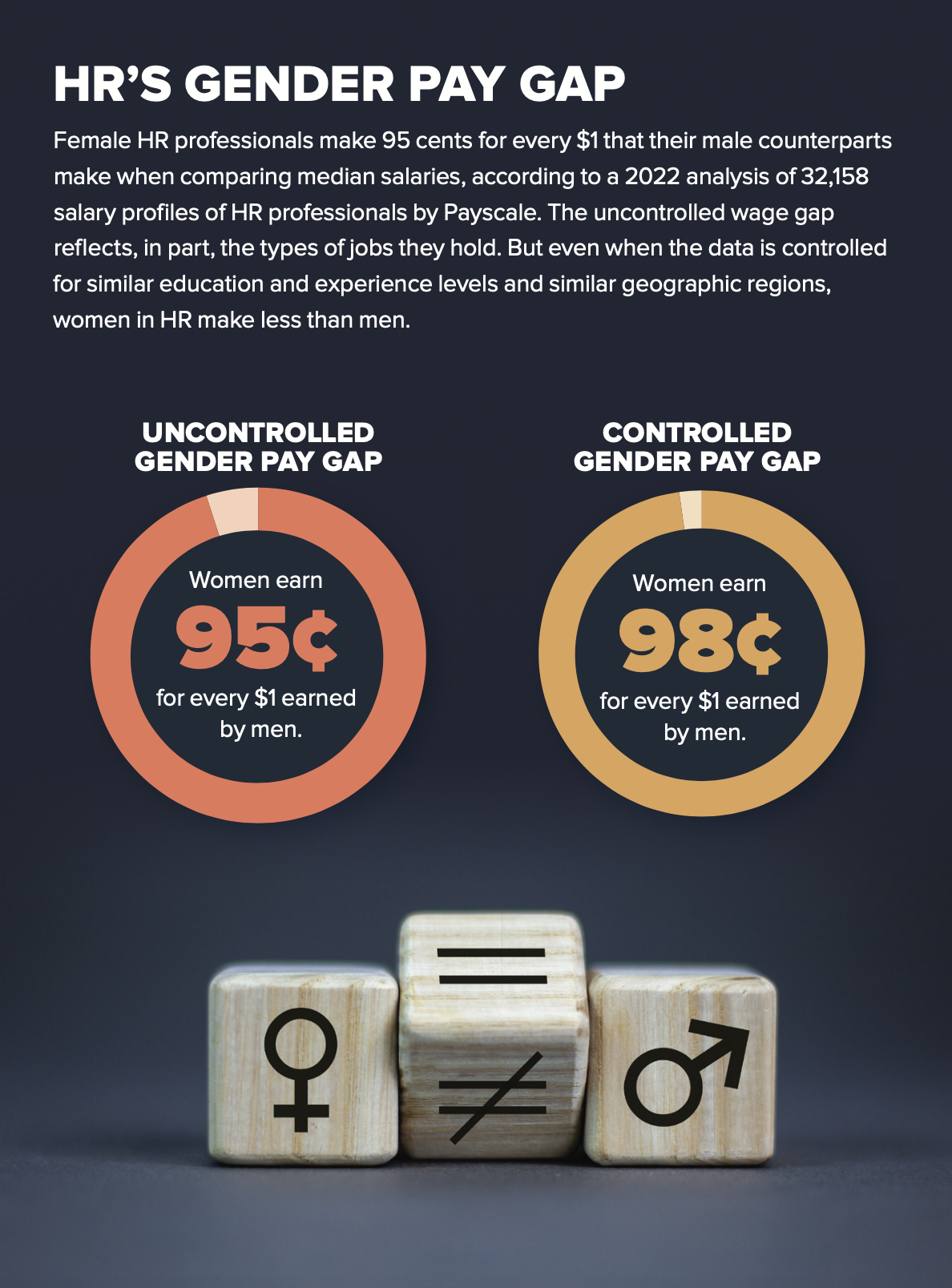

Wage gaps shrink when comparing white men with either women or men of color doing the same job. When controlled for job responsibilities, education and experience, women earn 99 cents for every dollar earned by a man. Black men are on par with white men, while the pay of Hispanic men falls short by a penny, according to Payscale. Federal laws require equal pay for equal work.

Pay equity advocates say the overall pay gap is a better barometer of salary equity because it illustrates how women and people of color are overrepresented in relatively low-paying jobs such as teacher and home health care worker. It also highlights that corporations still don’t have enough women and people of color in senior roles with high salaries.

“It’s important to understand what representation is at all levels of a company and then look at pay associated with that, because that then allows us to really understand if people are being treated fairly and equitably at all levels of the company,” says Alison Omens, chief strategy officer at JUST Capital.

Government Intervention

The U.S. has one of the worst records in the developed world for reporting gender pay gaps, according to Equileap, an Amsterdam-based nonprofit that studies gender equality. Countries with the best records, such as Spain, Italy and the U.K., have laws that require disclosure.

“If the United States wants to see more pay transparency, it’s going to have to put legislation in place,” says Diana van Maasdijk, CEO of Equileap.

In March, President Joe Biden signed an executive order aimed at limiting or prohibiting federal contractors from considering previous or current compensation in employment decisions. The Office of Personnel Management is also expected to propose a regulation that will bar the use of salary history in hiring and setting pay for federal employees. Numerous cities and states already have such prohibitions, and many companies have stopped asking for the information even without legislation.

Experts agree that banning employers from asking about applicants’ pay history would be a significant step toward achieving pay equity. Knowing a job candidate’s salary allows an employer to offer the individual more than they currently earn but less than the company is willing to pay.

So far, state and local governments are driving the charge for pay transparency. However, a New York City law requiring employers to post salary ranges on job ads has been postponed until November after employers pushed for changes.

“We want to do it the right way that doesn’t cause undue harm to employers,” says Nantasha Williams, a New York City Council member who co-sponsored the legislation. “The hope is that people who have been historically marginalized as it pertains to wages will have more line of sight to better negotiate for higher salary.”

Including salary ranges in job postings is viewed as particularly employee-friendly, though not all city and state transparency laws require it. Some laws require employers to disclose salary ranges only when asked or at certain points in the interview process. Regardless, many business leaders remain staunchly opposed to any kind of legislation.

Consider what happened in Colorado last year: After the state enacted a regulation that forbids asking about salary history, requires that salary ranges be included in all job ads and demands that companies post all promotion opportunities internally, companies including Johnson & Johnson, McKesson Corp. and CBRE Group Inc. posted ads for remote job opportunities that said Colorado applicants wouldn’t be considered. The Rocky Mountain Association of Recruiters sought an injunction against the law, but a federal judge denied the request.

Despite the fury, rather than aggressively penalizing companies that aren’t in compliance, Colorado has instead been sending out warning letters, according to Elizabeth S. Wylie, a Denver-based partner at law firm Snell & Wilmer. She says she has been advising clients to use the law as an opportunity to discuss their pay strategies with employees and listen to workers’ career goals.

“This is a trend that is not going away,” Wylie says.

Difficult Conversations

Conversations about pay transparency can be uncomfortable, and getting managers ready for them was a major focus of Denver-based Ibotta as it prepared for the Colorado law’s enactment, says Marisa Daspit, chief people officer at the cash-back rewards app company. Conducting pay audits and studying market research were also key.

“We have had to get a lot more comfortable having the conversations and helping people understand how their compensation is determined,” Daspit says. “While nobody really wants to have this conversation, I’d rather have that conversation and have people feel like they’re fairly compensated.”

One of the trickier parts of the law was figuring out how to handle promotions that were given as rewards for hard work, Daspit says. For example, when an employee was elevated from accountant to senior accountant, company leaders decided to post the newly created role even though it didn’t result in a new job opening.

Still, employees applied. “In some cases, it provided us insight into someone we didn’t know had an aspiration for a larger role or more responsibility,” Daspit says. “I will not lie and say it’s all been wonderful. You do have people who apply who are not ready and have to have conversations with those folks about what it’s going to take to get them ready.”

Managers also had to explain to employees why they fell into a certain part of the salary range and address concerns from those who believed they were underpaid when they saw ads at other companies that offered better compensation for positions with similar titles.

Overall, Daspit says, the law has led to more frequent and more productive discussions about compensation. She tells managers that employees “are having them, so you might as well have them, too.”

Only the Beginning

Salary information is more widely available than ever. It is broadcast on sites such as Glassdoor and sometimes even in company break rooms, at least among younger workers. Nearly 90 percent Generation Z workers (employees up to age 25) say they are comfortable discussing their salaries, compared with 53 percent of Baby Boomers (those between the ages of 58 and 76), according to an April 2022 Visier report. Moreover, one-third of respondents from Generation Z say they talk about pay with co-workers in the same role.

Employers may find that such discussions can help them retain employees in today’s tight labor market. A desire for more pay is a major reason people look for jobs, and 57 percent of workers who are paid at market rate—along with 42 percent of those who are overcompensated—believe they are underpaid, according to a Payscale study.

Still, transparency isn’t a magic pill that will automatically and easily correct pay gaps. Buffer, a fully remote company headquartered in San Francisco, has been posting the names, titles and salaries of its employees on its website since 2012, and yet the social media marketing company only reached a gender pay gap of less than 1 percent for the first time this year. In 2019, men at Buffer earned 15 percent more than women.

There were a variety of reasons for the gap—and for its closure. For example, with only 84 employees, one highly compensated individual could have an outsized effect on averages. In addition, Buffer’s staff in 2019 was made up of more men, and they were in higher positions. Over the years, the company made a more concerted effort to hire women in leadership positions by using inclusive language in its job postings, placing the ads on websites targeting a diverse applicant pool, offering paid family leave and providing unconscious-bias training. Adjusting cost-of-living bands also eliminated some of the gap.

“We have made huge strides and reduced the gap over time because we’ve been able to bring awareness to transparency,” says Buffer’s director of business operations, Jenny Terry, who is also in charge of HR.

Terry believes that if companies are serious about closing their pay gaps, they must acknowledge the possibility that different groups may be paid differently and then must work to end the disparities.

“It’s not benchmarking [salaries] that is holding them up,” Terry says. “If there is a desire to move toward transparency, it does need to be part of their core values.”

Theresa Agovino is the workplace editor for SHRM.

Photo Illustrations by Neil Jamieson.