She didn’t understand why he was staring at her.

Marissa, a 27-year-old Web developer, joined a group of co-workers for lunch in their company’s breakroom in Winter Park, Fla., in February 2020. She viewed the break as much-needed relief from a stressful morning working on a new website.

Good vibes filled the room as everybody enjoyed one another’s company. But the young tech professional, who is Jewish, noticed a male colleague staring and smirking at her from across the table. Even when she looked away, he maintained his gaze.

Annoyed, Marissa jokingly asked him if there was food on her face.

“He responded with a comment about my physical appearance and the way Jewish people in general look,” she recalls. “I remember just sitting there, stunned. I couldn’t believe it.”

It wasn’t the first time Marissa had experienced antisemitism. Growing up, she had endured harsh comments about her Jewish heritage from friends and even adults. But this was the first time it had happened in a professional setting. And the worst part, she says, was that no one else seemed to care. A couple of her co-workers even laughed.

Marissa didn’t report the incident to human resources because the person who made the remark was well-liked within the company, she says. And she was embarrassed by the situation.

“It’s one of those things that you get over, but you never forget,” Marissa says. “People think they’re being funny when making offensive comments, but they’re still hurtful. I don’t think they fully realize what those comments can do to someone.”

Racism and discrimination are rife in U.S. workplaces. The advent of the Black Lives Matter movement, the increase in anti-Asian-American violence and other recent racial atrocities have inspired companies to speak out against bigotry and strengthen their diversity, equity and inclusion (DE&I) programs.

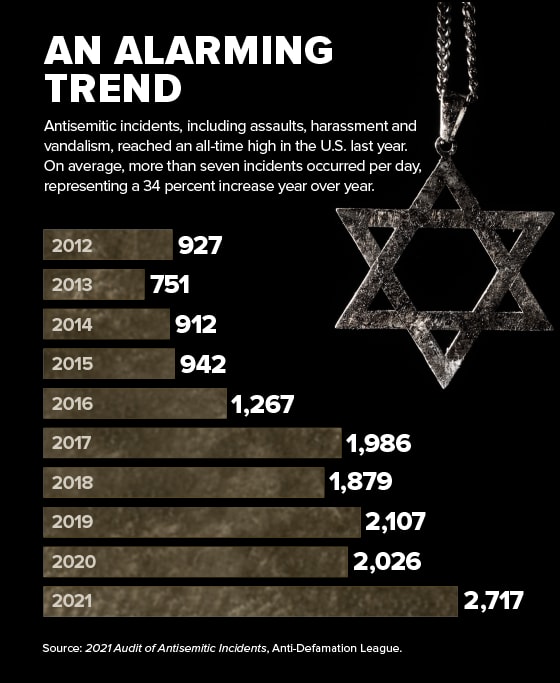

But bias aimed at Jewish employees often goes unnoticed, despite a recent rise in antisemitism. Anti-Defamation League (ADL) data shows that business establishments were the fourth most common site of antisemitic incidents in 2020, with the incidents ranging from verbal abuse to physical intimidation.

More than half of Jewish workers reported dealing with workplace discrimination in their careers, according to a 2022 report by Rice University’s Religion and Public Life Program. Respondents said they had experienced harmful comments, stereotyping and social exclusion.

The COVID-19 pandemic hasn’t helped. Vlad Khaykin, national director of antisemitism programs at the ADL, says hate acts tend to increase during times of collective anxiety and uncertainty. Malicious words and actions can be spurred by pandemics, civil unrest, political instability or economic downturns.

“Human beings seek to identify the source of the threat, the source of suffering or anxiety, and antisemitism functions as a conspiracy theory which provides simplistic answers to what are complex, often systemic, problems in the form of a Jewish scapegoat,” Khaykin says.

Social media doesn’t help either.

The Center for Countering Digital Hate, a research organization, found 714 posts containing anti-Jewish sentiments on social media platforms such as Facebook, YouTube and Twitter between May and June 2021. Collectively, these posts had been viewed at least 7.3 million times.

Some individuals have conjured conspiracy theories about Jewish people, such as the false claim that Jews created the coronavirus with the sinister purpose of then being able to profit from developing an antidote.

In December 2021, for example, dozens of flyers containing this conspiracy theory were scattered throughout California and North Carolina, according to a Newsweek report. Both Jewish and non-Jewish residents woke to discover the messages in their yards, placed in plastic bags weighed down with pebbles. As of January 2022, police were still investigating the incident.

Antisemitism Goes Mainstream

High-profile incidents of antisemitism have dominated news headlines in recent months.

In 2021, Google fired a prominent executive after he posted a 10,000-word manifesto admitting to past antisemitic behavior. The company also reassigned its global lead for diversity strategy and research after discovering his now-deleted 2007 blog post filled with anti-Jewish messages.

That same year, comedian Nick Cannon promoted antisemitic conspiracy theories on his podcast. His employer, ViacomCBS, immediately fired Cannon from the improv TV show “Wild ‘N Out” and condemned his remarks. He later apologized.

And Whoopi Goldberg, co-host of the hit TV show “The View,” caused a stir in February when she incorrectly stated to millions of viewers that the Holocaust “isn’t about race.” Although she apologized, the show’s broadcast company, ABC, suspended her for two weeks.

“Recent remarks by public figures are a reminder that antisemitism is far more widespread than we would like to believe,” says Andrea Lucas, a commissioner at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “These types of remarks can lead to the misguided notion that such antisemitic comments are acceptable. Antisemitism in any form is unacceptable and should be condemned.”

Expressions of Antisemitism

The antisemitism found in Hollywood and social media reflects that of corporate America, says Jonathan Segal, an employment law attorney in Philadelphia who has witnessed the stereotyping of Jewish lawyers as shrewd, cunning or somehow psychologically stronger than others who practice law.

Segal, who is Jewish, has been told that he doesn’t “seem Jewish” and that to negotiate a lower price he should “Jew down the other side.”

“I’ve received this phone call: ‘I’m looking for a good Jewish lawyer, if you know what I mean,’ ” Segal recalls. “They think it’s a compliment. It’s the implication that you’re somehow stronger than the average lawyer. It’s like comments that Jews make the best accountants. It’s false praise.”

Often the antisemitism is more explicit. A software sales executive who requested anonymity once worked for a company in southern California. Not many on the management team knew he was Jewish, though his direct manager knew.

During a meeting, the team was discussing a conference that was being held during Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the year in Judaism. A manager suggested that the sales executive attend. He said he couldn’t attend due to a scheduling conflict.

His boss implored him to work out the conflict and attend because important clients would be there.

“I said that the conference fell on a Jewish holiday, and he replied, ‘Right, I forgot you were Jewish. Well, I think God will forgive you for going, but I’m not sure I’ll forgive you for not going,’ ” he says. “Fortunately, another manager later agreed to go in my place, but that ruined my relationship with my boss, and I soon found another job.”

?  |

|

Types of antisemitism, according to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission:

|

History of Antisemitism at Work

Workplace antisemitism isn’t a new development.

In the 1940s, during the height of World War II, thousands of Jews who survived the Holocaust came to the U.S. for freedom and opportunity. But many of these individuals endured implicit hate and discrimination because of their Jewish heritage.

For example, a study published in 1956 examined workplace discrimination among Jews. Researchers found that industries such as commercial banking, automobile manufacturing, shipping and transportation, agriculture, and mining would not hire Jewish workers.

Around this time, some help-wanted newspaper ads in the U.S. requested candidates who were “gentile” or “gentile-preferred.” Some Jewish lawyers in the mid-20th century started their own businesses because many law firms actively excluded them from employment.

In some fields, such as medicine, Jewish practitioners were also limited by anti-Jewish graduate school admissions restrictions. Aspiring Jewish doctors often had to enter other fields or change their names to avoid this discrimination.

Even Ivy League institutions established quotas limiting the number of Jewish students they would accept.

“Within many workplaces, there was an understanding that one should not act ‘too Jewish,'” said Kenneth L. Marcus, the founder and leader of the Louis D. Brandeis Center, an institution dedicated to advancing the civil and human rights of Jewish people. “This led many Jews to ‘cover’ or mute their ethnic characteristics to avoid sticking out.”

Segal has encountered Jewish clients who refuse to discuss their religion in the workplace and other public forums due to fear of criticism. This has caused many Jews to downplay their heritage rather than vocalize their pride.

“There’s a trend for Jewish workers to stay below the radar, even to this day,” Segal says.

Segal experienced antisemitism at a young age. As a college student in the 1980s, he worked at a candy store in a local mall. He loved the job, and he enjoyed working with his colleagues. But they often used Jewish tropes in his presence.

“They made jokes about Jewish money and some other ugly comments about Jews,” Segal recalls. “I felt conflicted because I liked them, but I hated what they said.”

Segal eventually decided to advertise his Jewish heritage. He asked his parents for a Jewish star to wear to work. If they were going to continue to make those comments, he wanted them to know that a Jew was in their presence.

Upon seeing the star, his co-workers stopped making the comments.

“I still believe the comments were born of ignorance rather than hate per se,” Segal says. “That’s why I think education is so important.”

Cases of ‘Zoombombing’

Antisemitism has entered the modern age, with haters using updated technology to offend.

In 2020, dozens of cases of “Zoombombing” occurred—114 of which targeted religious, educational or cultural webinars conducted by Jewish institutions, according to ADL data.

Congregation Tifereth Israel in Columbus, Ohio, was conducting Shabbat morning services on Zoom in April 2020 when the session was unexpectedly interrupted by loud music, offensive images and antisemitic content. As many as 100 worshippers witnessed this “Zoombomb.”

These interruptions continued to occur during the synagogue’s virtual services about two to three times per month throughout the year.

“In the moment, it was frustrating and disorienting,” says Alex Braver, associate rabbi at Tifereth Israel. “It’s hard to be able to really focus on being a spiritual leader or teaching a class while also trying to make sure offensive content and disruptive people are kept out.”

Eventually, the synagogue implemented additional security measures to protect its services from such intrusions. But Braver doesn’t expect antisemitic incidents to completely go away, given the rise in hate incidents against Jews in recent years.

“We can only do our best to continue to stand for what we believe in, to be welcoming and kind, and to fight for a better world for everyone,” he says.

Antisemitism, like all kinds of prejudice, can erode a healthy work culture because it normalizes biased attitudes and reduces the chances of creating a truly diverse and inclusive environment. Discrimination in the workplace can also cause psychological harm among victims.

Victims of antisemitism often isolate themselves as a coping mechanism, according to a 2021 report published in the International Review of Victimology. They might remove themselves from social circles, avoid company gatherings or change jobs.

Those who don’t make changes to their social life may limit their self-expression when in public, the report found. They might be less likely to speak about their Jewish heritage to their friends or colleagues to avoid potential ridicule.

A 2017 report by the Royal College of Psychologists found that antisemitism can create short-term effects for its targets, such as shock and anger, as well as long-term consequences on a person’s self-esteem and psyche.

“[Antisemitism in workplaces] can lead to alienation, demoralization, loss of jobs and, in the worst cases, it will lead to a culture of hate that may give rise to physical violence, inside or outside of work,” Lucas says.

‘Human beings seek to identify the source of the threat, the source of suffering or anxiety, and antisemitism functions as a conspiracy theory which provides simplistic answers to what are complex, often systemic, problems in the form of a Jewish scapegoat.’

—Vlad Khaykin

Carefully Audit DE&I Programs

The struggles of Black, Asian-American and LGBTQ individuals have understandably dominated discussions within many DE&I programs, given the rise of discrimination and violence against these groups in recent years.

However, the experiences of other underrepresented groups, including Jewish and Muslim workers, should not be ignored, says Neal Goodman, president of Global Dynamics Inc., a workplace consulting firm in Aventura, Fla. All forms of bigotry, prejudice and bias should be addressed, Goodman says.

“Organizations should start with a discussion of the many dimensions of diversity, including religion, race and gender,” he explains. “A discussion of bias, bigotry and prejudice is critical. Within that context, everyone in the room should be able to share their own story of experiencing bias to raise awareness [of these issues].”

Simply adding mentions of antisemitism to existing programs doesn’t always suffice, Goodman says. Some training modules are built on binary assumptions, dividing employees into two groups: white people and people of color. Marcus explains that many Jewish workers don’t fit comfortably into either category because people of all races can be Jewish.

He says some Jewish workers feel that certain DE&I training imposes upon them an identity that they haven’t chosen and that doesn’t reflect their lived experience.

“When Jews are viewed as privileged white oppressors, they may feel that their Jewish identities are erased and that their co-workers are viewing them through stereotypes about Jewish conspiracy and power,” Marcus says. “[Employers] must use DE&I as a tool, but they must also recognize that this tool has sometimes been compromised.”

DE&I programs can be productive if they are managed correctly, Lucas notes. Companies should carefully audit these initiatives and provide implementation training to ensure they do not contribute to antisemitism—including through assumptions or stereotypes of power, privilege, racial identity or conclusions based on racial or ethnic disparities.

“Inclusion needs to be truly inclusive,” Lucas says. “Religious discrimination, in any form, is always unacceptable.”

Khaykin believes businesses play an important role in stopping the spread of antisemitism and protecting the welfare of Jewish employees. He says companies should consider:

- Establishing, supporting and working in partnership with Jewish employee resource groups that can help to inform actions and policies to create more safe and equitable work environments for Jewish people.

- Creating and identifying opportunities for education about Jewish people, culture, history and religion, as well as antisemitism.

- Reviewing policies and ensuring that they do not marginalize Jewish people. This includes matters such as dress codes and out-of-office policies.

- Ensuring clear HR policies, mechanisms and communications around how to report incidents or other issues and seek a redress of grievances.

- Reviewing company language, both internal and external, to ensure communications are equitable and inclusive.

Business leaders should speak up unequivocally in support of Jewish employees and against antisemitism, Lucas says. This might include drafting clear guidance about inappropriate statements and postings online—a go-to platform for spreading antisemitic messages.

HR professionals are often on the front line of protecting an employer’s brand. Employment attorneys say companies can fire an employee for engaging in hate speech or making disparaging comments about protected categories of race, religion and gender.

It is incumbent upon an organization’s decision-makers to immediately address antisemitic comments made by an employee, Marcus says. Failing to act on the situation can jeopardize a company’s credibility.

“When these practices are tolerated,” Marcus explains, “they send a message that is antithetical to the goals of diversity, equal opportunity and inclusion.”

Matt Gonzales is an online writer/editor for SHRM who focuses on diversity, equity and inclusion topics.

Explore Further

SHRM provides resources and information to help business leaders better understand the impact of discrimination on their employees and workplaces.

Combating Antisemitism in the Workplace

Examples of antisemitism in the workplace include firing, not hiring or paying someone less because the person is Jewish; assigning Jewish individuals to less-desirable work conditions; refusing to grant religious accommodations; and making anti-Jewish remarks.

SHRM Toolkit: Navigating Religious Beliefs in the Workplace

Everyone has a viewpoint on religion or spiritual beliefs, be it atheistic, dogmatic, academic, indifferent or somewhere in between. Managing these various points of view with respect and equity can create a culture where employees are happier and more productive, while also making legal compliance easier for the employer.

Accommodating Religion in the Workplace Training

This sample presentation is intended for delivery to supervisors and other individuals who manage employees. It is designed to be presented by an individual who has knowledge of the law and best practices regarding religious issues in the workplace.

SHRM Toolkit: Managing Equal Employment Opportunity

Public policy regarding equal employment opportunity (EEO) is expressed in constitutions and, more particularly, in anti-discrimination laws. In the U.S., these laws exist at the federal, state and local levels. EEO laws vary greatly from one place to another in terms of the employers or other entities they cover, the particular classes of persons they protect, the transactions they regulate, and the type and extent of legal remedies they provide for.

Is It Discrimination or Just a Failure to Communicate?

The overwhelming majority of discrimination claims would not happen if proper communication was maintained. Moreover, the problem often doesn’t exist simply at the manager or supervisor level—it extends to HR.

Quiz: Can You Recognize Workplace Discrimination?

Several federal laws include provisions intended to prevent workplace discrimination. Compliance with the letter and spirit of these laws can seem complex and fraught with intricate processes. Find out how well you know key protections of major laws with this quiz.