?Editor’s Note: SHRM has partnered with Harvard Business Review to bring you relevant articles on key HR topics and strategies.

Statistically, you will likely change jobs several times before retiring. In fact, a Pew Research survey estimated that 30% of American workers changed jobs in 2022 alone, most for higher pay. But doing so can be treacherous for your ability to retire when you want and with the lifestyle you want. Why? Because too many people cash out their entire 401(k)s whey they leave a job — and employers do little to prevent it.

According to Vanguard data from 2021, the median 401(k) account for a 55- to 64-year-old was $89,716. That won’t take a middle-class person very far, even with partner retirement savings, Social Security and other sources of retirement income. These low balances arise despite an increased emphasis from employers, the financial services industry and personal finance gurus on helping employees accumulate retirement savings through employer-sponsored retirement plans. Many firms now have generous match rates aimed to attract and retain the best employees and to assure financial security in retirement.

However, the focus on savings accumulation during employment misses a key fact: In the U.S., employees can cash out at any time they are working or when they leave a job. Among developed economies, only the U.S. allows firms to present this option to a departing employee. Employees also pay income tax, and for withdrawals before age 59.5, they’ll pay 10% in penalties.

Too often, departing employees cash out their 401(k)s when they change jobs, dissipating all that they saved while working. Few employers see this as a problem, but almost no decision an employee makes can so undercut retirement preparedness.

Why and When People Cash Out Their 401(k)s

To better understand how prevalent 401(k) cash outs are when someone leaves a job, our recent research studied 162,360 exiting employees in the U.S. covered by 28 retirement plans. They left their firms in a three-year period before Covid-19, from 2014 to 2016.

Shockingly, 41.4% of employees cashed out 401(k) savings on the way out the door. Equally surprising was that 85% of those who did cash out drained the entire balance.

Did they need to? It’s hard to know for sure, but it is by no means a logical conclusion that cashing out is a good or necessary response to leaving or losing a job. We see this both in our research and in more recent data. For example, we estimated that only 27.3% of the employees we studied had lost their jobs (as opposed to leaving voluntarily). And other countries require many months of unemployment and evidence of clear hardship before allowing someone to tap defined contribution retirement savings.

Further, in the U.S., industry studies show that cashing out stayed flat or slightly declined during the Covid pandemic despite massive increases in job loss. How did all those new waves of unemployed people cope? They relied on a combination of temporary lifestyle changes, gig work and government benefits, heeding calls like that from Carrie Schwab-Pomerantz, president of the Charles Schwab Foundation, who counseled people to avoid using relaxed rules on withdrawals during the pandemic under the CARES act:

“Even if it’s possible to borrow from your 401(k) or take a distribution … consider this a last resort. While present circumstances may be difficult, I’d counsel anyone to avoid jeopardizing their future retirement unless absolutely necessary. You may not appreciate the full consequences until much later.”

The 41.4% cash-out figure at job exit in our data also dwarfed the number cashing out during their years of employment. While employed, people had plenty of opportunities to have a cash crunch from circumstances like partner job loss, medical emergencies, weddings to plan and impending college bills, and they faced the same taxes and penalties for early withdrawal. Yet only 7% cashed out via hardship withdrawal and 3% via 401(k) loans that were not repaid on time. We calculated that dollar losses to cash outs at job change were 12.4 times what these 162,360 employees cashed out during their average 6.6 years at their firms.

So why do so many people cash out at a job change specifically and undermine their retirement security? Why not roll their 401(k) balance to an IRA or Roth IRA, keep money in their employers’ plans or transfer assets to new employers’ plans if available?

The problems come from bureaucracy and psychology. Employers delegate all communication when an employee leaves to financial services firms like Fidelity, Vanguard, TIAA or Alight, who administer their plans. These plans send anodyne form letters to employees with facts about what their options are, but not advice. In addition, the form letter, by law, allows employers to give less attractive options to exiting employees if they have lower balances. For example:

- Most employees with balances less than $1,000 are automatically issued a check of their savings minus income tax and 10% penalties, with no other options offered.

- Most employees with balances between $1,000 and $5,000 are given two other options to cashing out: to roll over assets into a qualified IRA or to transfer to a new employer’s plan.

- Most employees with balances over $5,000 are given three options to cashing out: to keep their money in the current plan, to roll over assets into a qualified IRA or to transfer to a new employer’s plan.

Critically, these form letters make the option to cash out far more front-of-mind than it was during years of employment. They turn psychologically illiquid retirement savings into a source of ready cash. When exiting employees are nudged to consider the option to cash out, it becomes quite appealing to spend what had previously been seen as an untouchable source of retirement security. No wonder so many more cash out when changing jobs than when working.

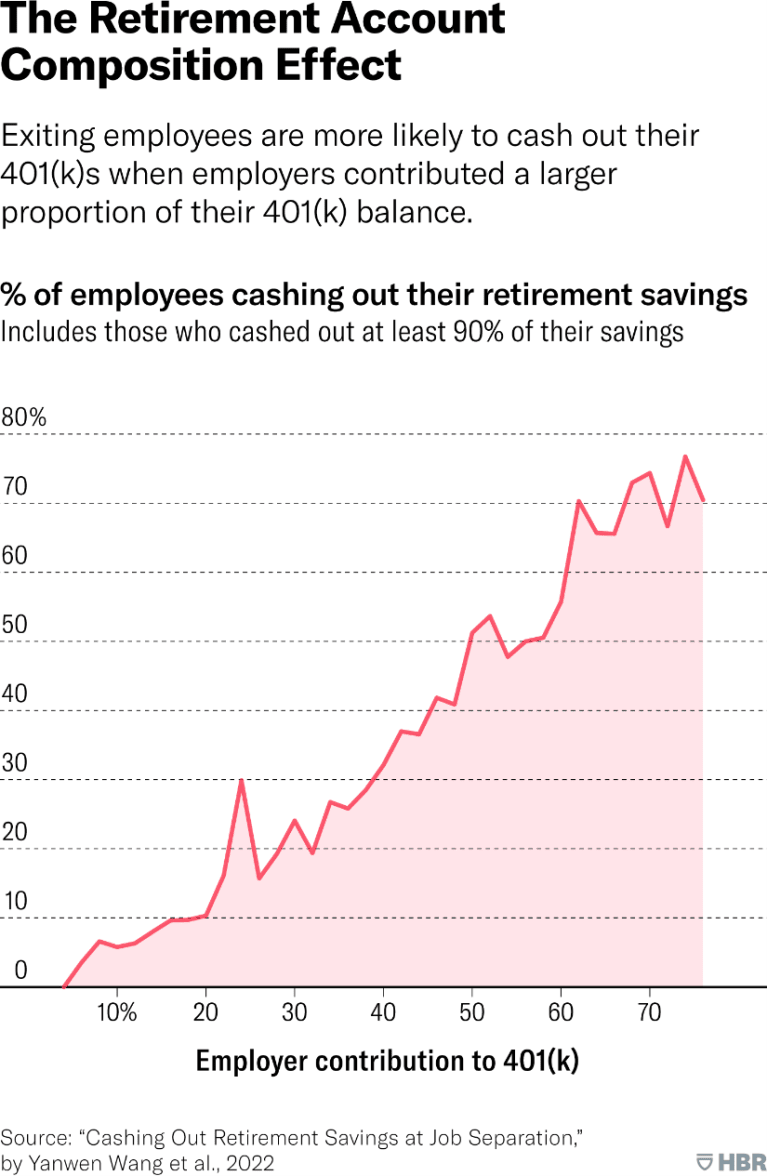

We also find people act on that temptation to cash out more strongly when they contributed proportionally less to their total 401(k) balance — holding constant the size of the balance and other employee characteristics. We call this pattern the “account composition effect.”

The pattern we observed was the same for employees with higher or lower 401(k) balances, higher or lower income, men or women, older or younger employees and those who left the firm in months with high or low turnover. All told, the more the balance came from the employer, the more people treat their savings as “house money” or “free money” when prompted at job change to consider the option to cash out.

How Employers Can Help Departing Employees

The lesson from our findings is not that employers should contribute less in employer matches. The lesson is that a socially responsible employer should pay attention to employees when they are leaving the firm, too. Firms with more generous retirement matches obviously intend to provide for employee financial well-being years down the road. And most know that many of their current employees will change jobs — several times — before their eventual retirement. Employers’ indifference to cash-outs is undermining their investment in their employees’ futures. Right now, cashing out is the path of least resistance. People choose what is easy, not what is wise.

Employers could take steps to dramatically improve employees’ retirement security at a very low cost to them. For example, there is increasing recognition that cashing out is more likely if people lack emergency savings. The new Secure Act 2.0 that became law in December allows employees to automatically allocate up to $2,500 per year to pay for emergency expenditures without raiding their retirement fund. When onboarding new employees and explaining retirement benefits, employers could encourage use of these accounts and forewarn new employees of the danger of cashing out at the point they later change jobs.

Employers could also contract with their financial services partners to provide Web-enabled “just-in-time financial education” around preserving retirement balances during a job change, or pay for a session with a financial advisor. Similarly, employers could pay financial services firms to conduct an exit meeting to help individual employees evaluate if they should keep their assets in their current plan, transfer assets to their new employers’ plan or have their 401(k) balance automatically transferred to very low-cost Roth IRA index funds. All of these options preserve employee retirement security and avoid 10% penalties — and all of these options should be easier than cashing out.

Along these same lines, we recommend that firms stop automatically cashing out employees with small balances. There are some emerging ways to make this easier; for example, a new “auto-portability” initiative by Retirement Clearinghouse automates the process of transferring balances under $5,000 from the current employer to the new employer’s plan if both employer plan sponsors are served by major financial services firm.

If industry does not solve this problem of retirement savings being drained at job change, neither employers nor financial service firms may like what comes next. Governments might step in to create new systems more like those in other parts of the world, such as in Australia. There, all firms must contribute the same amount, all employees must contribute the same amount and the account stays with employees when they change jobs — and employees cannot access their balance until after prolonged unemployment.

We think the more likely scenario is that businesses solve the problem, with employers working with financial services firms to make small changes with dramatic potential to change employee retirement readiness. There are big benefits to the employers in a competitive market for talent and to financial services firms who take the lead in solving this pressing societal problem.

John G. Lynch is University of Colorado Distinguished Professor at the Leeds School of Business, University of Colorado-Boulder and Executive Director of the Marketing Science Institute. From 2017-2020 he served on the Academic Research Council of the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Yanwen Wang is Associate Professor and Chair, Marketing and Behavioral Science Division and Canada Research Chair in Marketing Analytics. Muxin Zhai is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Finance and Economics at Texas State University’s McCoy College of Business.

This article is reprinted from Harvard Business Review with permission. ©2023. All rights reserved.