?Edie Goldberg was caught off guard when her boss at a former employer approached her with a surprising request. At the time, she was responsible for designing and scoring job candidate assessments for a San Francisco Bay Area consulting firm. Her boss wanted her to temporarily lower the pass score on a test so that a client’s relative would qualify for a job. Goldberg refused, finding the move unethical as well as legally risky, since it had the potential to trigger a discrimination complaint.

Goldberg says she had a great deal of respect for her boss before the incident, but his request soured her on the organization. She left soon afterward.

As HR professionals know, rocking the boat—especially when it means pushing back against a boss’s request—carries some very real career risks. Getting fired may be the most extreme consequence of speaking truth to power. Other repercussions include being ignored or organizationally isolated.

“As an HR professional, you need to decide when that risk crosses a threshold of your own moral compass and is an action you are not willing to be part of,” says Goldberg, who now runs her own HR consulting firm specializing in human capital management and organizational development. “That can be a career-sacrificing move, and you need to be aware of that.”

Despite odds that may seem impossibly low, HR practitioners can be successful going head-to-head with management—without putting their jobs on the line. In addition to helping you sleep better at night, courageously speaking out may raise your value within the organization and strengthen your relationship with your boss.

Confronting Issues

An HR director in Oregon says she was reluctant to confront her organization’s chief executive officer about his creepy habit of staring at her breasts. (Due to the personal nature of the issue, she asked not to be identified by name.) She knew the boss did not take criticism well and had a history of lashing out against detractors. But she felt compelled to speak out after several female employees complained to her about the same problem.

“I just pulled [the CEO] aside and said, ‘I’m sure you didn’t know you were doing this, but I’m sure you’d want to know,’ ” she says.

Although the executive denied the allegation, he now keeps his eyes where they belong, the HR director says. Just as importantly, he doesn’t seem to have held a grudge.

Ronda Griffin, an HR manager for a St. Louis-based construction company, faced a different but equally challenging quandary at a previous organization. Griffin had to speak repeatedly to a former boss whose treatment of employees was being viewed as abusive. In one notable instance, the boss pushed an employee out of the way during a fire drill.

“I wanted [the boss] to speak and interact with employees more mindfully and respectfully,” Griffin says.

She adds that she feels good about speaking out, even though she questions whether doing so had any lasting impact on her boss’s behavior. “I think every HR professional needs to be able to develop as deep a collaborative and supportive relationship as possible with their CEO,” Griffin says. “We all want the organization to succeed.”

Acting Courageously

Everyone benefits when employees speak out about workplace problems, according to James R. Detert, a professor at the University of Virginia’s Darden Graduate School of Business. His book Choosing Courage: The Everyday Guide to Being Brave at Work (Harvard Business Review, 2021) examines why and when people act courageously in the workplace. According to his research, employees are more creative and productive when they aren’t afraid they’ll be punished for rocking the boat.

Most acts of workplace courage don’t come from whistleblowers or organizational martyrs, Detert found. Rather, they come from respected insiders at all levels who take action—such as by campaigning for a risky strategic move, pushing to change an unfair policy or speaking out against unethical behavior—“because they believe it’s the right thing to do,” he says.

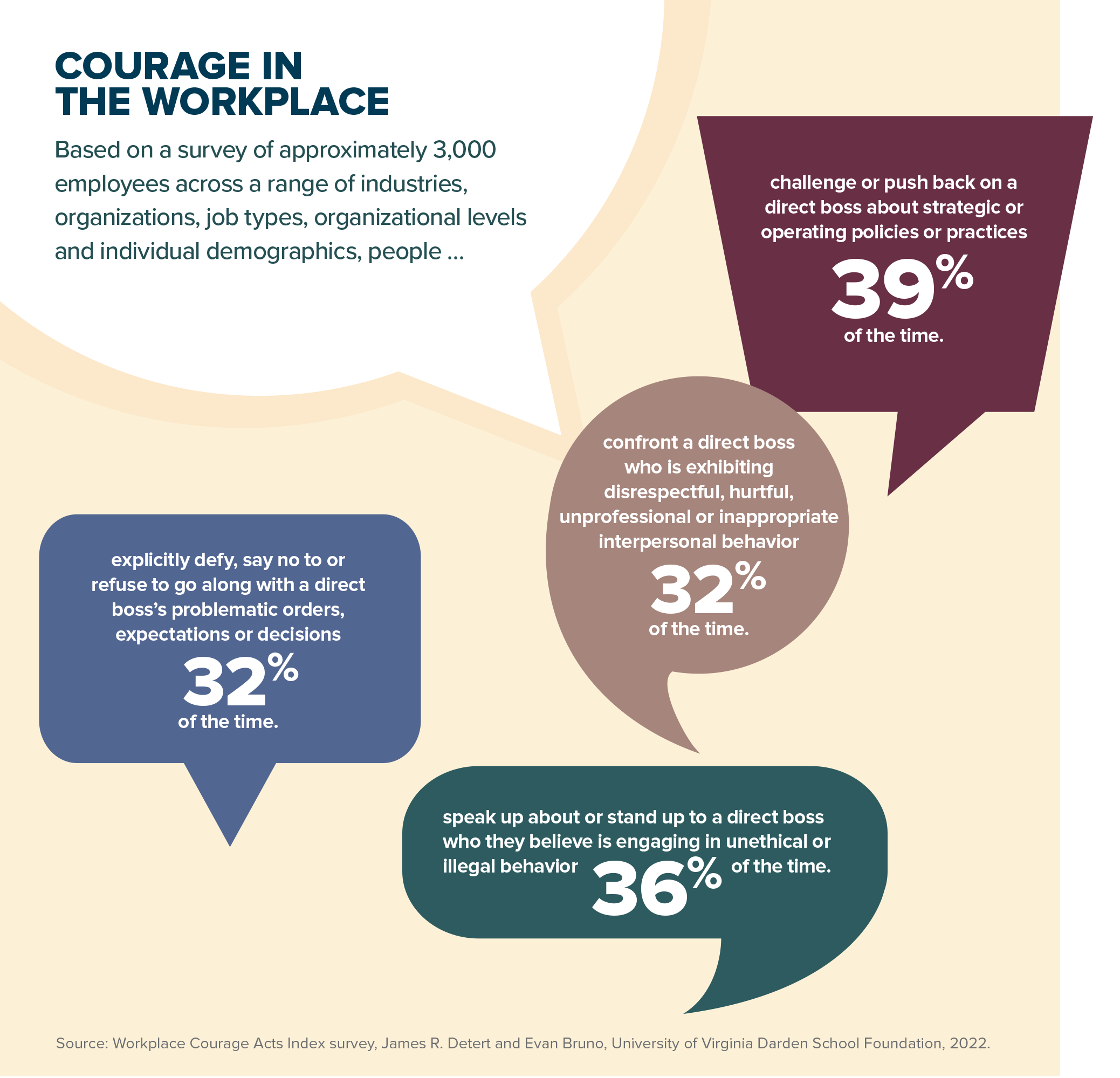

Unfortunately, but perhaps not surprisingly, most employees aren’t particularly eager to take on the boss. In fact, Detert found that people who believe their boss is engaging in unethical or illegal behavior speak up about it only 36 percent of the time. They defy a direct boss’s problematic orders or confront a direct boss who is exhibiting disrespectful or inappropriate interpersonal behavior less than one-third of the time.

The widespread silence is damaging for individuals as well as employers, Detert says, because it eats away at employees’ motivation and commitment and prevents organizations from discovering and addressing potential legal or ethical issues before they snowball.

“It’s like knowing that canaries are important in a coal mine,” he says, “but having created conditions where the birds don’t sing when they should.”

Maximizing Your Chances of Success

Getting the results you want from speaking truth to power requires being thoughtful about the way you communicate. The good news is that many effective communication techniques can be learned. Here are some tips from Detert and others for minimizing the risks that often accompany speaking out:

Lay the groundwork. People who speak out are most likely to get the results they want if they have already earned their boss’s respect, according to Detert. They have often “spent months or years establishing that they excel at their jobs, that they’re invested in the organization and that they’re evenhanded,” he says. Conversely, those who haven’t taken the time to gain their boss’s trust, or who have a reputation for selfishness or ill will, tend to be less successful.

Select the right time. People whose workplace courage has paid off are “masters of good timing,” Detert found. “They observe what’s going on around them, and if the timing doesn’t look right, they patiently hold off,” he says. Accordingly, if your boss is busy putting out other fires or if public sentiment isn’t with you, it might be more effective to deliver your message later.

Get your facts straight. Be sure to have evidence in hand to support your position or to back up any allegation you’re making, advises Mark Murphy, CEO of Atlanta-based leadership training firm Leadership IQ and the author of several books on workplace communication and talent management strategies. Avoid softening your message with words like “I feel,” since doing so suggests that your message is based on emotions rather than objective reality, Murphy says. And don’t just present your boss with bad news, he advises; instead, come armed with solutions to the problem you’re identifying.

Focus on the organization’s interests. Frame your concerns in terms of what’s best for the company, Goldberg says. If you’re confident your boss is on shaky legal ground, explain why you think that and what the consequences could be. “Widen the aperture,” she suggests, “so [your boss] sees the situation from different perspectives.”

Keep your emotions in check. There’s nothing wrong with being passionate about the issue you’re presenting to your boss, but displaying negative emotions such as anger and frustration can undermine your credibility. “Allow yourself to be informed [by emotions] but not held hostage by them,” Detert advises.

Pick your battles. Think about whether engaging in a potential battle is likely to help or hinder your ability to achieve larger goals. For example, consider whether securing resources to address one problem will make it harder to get a more important project funded later, Detert says.

Trust, but verify. Even if you’re confident your boss got the message you wanted to send, be sure to follow up, Griffin advises. Speak with other employees who have shared your concerns to confirm that the issue has been resolved, and summon the courage to check in with your boss to ensure there are no hard feelings.

Rita Zeidner is a freelance writer in Falls Church, Va.

Photograph by Isbjorn/iStock.